|

| Francis

Bacon |

|

|

|

| Painter

of a Dark Vision

|

|

|

|

--Inseparable

Art and Life?

--For

most of his many years it was simply not to speak or write of

Francis Bacon's private life, whispered to be not merely disreputable

but punishable, at least in his first half century, by sanctions

almost as harsh as those for treason and murder!

--Though

to critics of any sensibility it was obvious that his private

life was largely the source of imagery and energy in his paintings

and unquestionably crucial to his aesthetic development, there

were others who - through overwhelming prominence on the Arts

Council and our television sets, almost as celebrated as himself

for their performances as his interpreters - gave us a Francis

Bacon distorted and bowdlerised.

--In

their constructs he could discern little of himself, but in a

sense he was content with their dissembling, for it kept him camouflaged

and his private life remained largely private to the end.

--Though

he knew them to be in error, his conviction was that in time their

interpretations would be recognised as fraudulent, then discarded,

letting his paintings at last speak for themselves.

---

"Painting is its own language and is not translatable into

words".

|

|

|

|

|

|

--We

are speaking of two honest Bacons, with an unmentionable commercial

third bacon waiting in the wings.

--The

first was the kaleidoscopic, fragmentary Francis Bacon, wit, gossip,

gambler, drinker, traveller, willing supporter of such unlikely

young painters as Anthony Zych and Michael Leventis, social performer

and frivolous lost soul, and, in strong contrast, Bacon, the found

soul, the melancholy painter, utterly intense, the one a relief

from the other, though the onlooker could never quite tell which

of these lives he found the more unbearable.

--The

second Bacon was the painter preparing for the next commercial

exhibition, the repetitious Bacon, The Francis Bacon who had done

it all before, the idea and image stale, the clashing fields of

colour too much assured with practice, the drawing and construction

occasionally so casual as to deprive the painting of any intended

significance.

--The

third Bacon resorted to tricks and cyphers without meaning in

the early eighties to flat arrow-heads in black or white or red

that seem to act as jarring indicators - but of what? - and in

the late sixties to splashes of dense white paint strung across

the surface. |

|

|

|

--The

painter looks at you from behind his easel, a palette resting

on his left arm, a long thin brush in his right hand, the ends

of his moustache curling upward, the cross of Santiago on his

chest.

--This

is the self-portrait of the Spanish master Diego Velázquez,

on a page of an old art book smeared with a cloud of pink paint,

fleshy and warm, as if a human body had burst in the air above

it, the aftermath of a conversation between two great artists

across the centuries.

--It

was found among the forest of paintbrushes, dollops of pointillist

graffiti and enigmatically suspended bare light bulbs in the studio

of the artist Francis Bacon, a tiny space in a mews near South

Kensington tube station where he worked virtually everyday from

the early sixties until his death in 1992.

--Today

the studio is preserved in its entirety at the Hugh Lake Gallery

in Dublin.

--You

enter a chilly refrigerated room and peer through narrow windows

into the terrifyingly claustrophobic interior of the studio, that

has in its own right taken on the intense presence of a work of

Art.

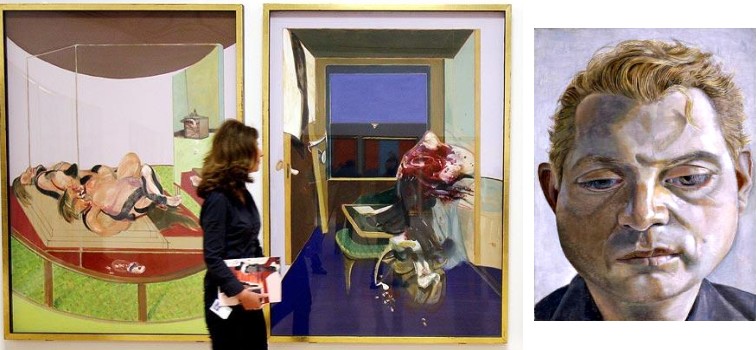

--Francis

Bacon joked that the daubs of paint he splashed on its walls were

his only abstract works.

--Now

the studio has become his only installation. It is fearsome with

its rust-flecked mirror, its gory detritus of paint cans and pigment.

--There's

an incredible power to this place and the creativity it commemorates.

The images on this article are part of its pungent archive of

a life lived in the magic space between mind and bodily act -

the life of a Painter of a Dark Vision!

|

|

| |

|

--Francis

Bacon didn't always tell the truth about his painting life. He

said he worked entirely by chance and accident, yet the secrets

of his studio revealed since his death, include plans for paintings,

rough sketches, and precise sources for images - such as the photograph

of a plucked and trussed chicken from the Conran cook book that

he directly copied on to a canvas.

--Evidently

his work was more thought-out and intellectual than he liked to

make it look. Further evidence is provided in Bacon's Incunabula,

a fascinating publication of the research materials from his studio.

That's the source of the pictures here. Its author, Martin Harrison,

says Francis Bacon's hoarded photographs of everything from physical

deformities to the faces of close friends, reproductions of Old

Master paintings and pages from magazines on cookery, golf and

soccer, appear to be essential to a proper understanding of his

aims and methods.

--Most

of all, though, and in an intensely moving way, these photographic

fragments are part of Francis Bacon himself, marked by his brush,

recycled through his enigmatic imagination. With their beaten

up, torn, stained scrappiness, you might almost imagine them as

digested and - to be Baconian about it - regurgitated or defecated

by him. |

|

|

|

--Take

that portrait of Velázquez. It is a souvenir of love. Francis

Bacon idolised this 17th-century portraitist of the Spanish court.

--How

is it, he eloquently wondered, that an artist can so accurately

illustrate the faces of real people and "at the same time

so deeply unlock the greatest things that a man can think and

feel"?

--He

collected books about Velázquez for their reproductions

and in talking about his favourite, a portrait of Pope Innocent

X, explained how "it haunts me, and opens up all sort of

feelings and areas of - I was going to say - imagination, even

in me".

--That

says a lot about the process of creativity these fragments reveal.

--Francis

Bacon looked at photographs and reproductions to unlock his imagination

- a thoughtful process but in no sense rational.

--Some

artists use drugs or drink to disinhibit themselves. Francis Bacon

was a legendary drinker but claimed he rarely used drink creatively.

--He

got drunk instead on visual stimuli - gorged on images. This is

the aftermath of a visual orgy.

|

|

|

|

--A

black and white photograph of a crowd being fired on in St Petersburg

in 1917, color close-ups of skin diseases from medical text book,

serial photographs of animal and human motion by the photographer

Eadweard Muybridge, art book reproductions of ancient Greek and

Egyptian sculpture and Michelangelo drawings next to photos of

wrestlers and boxers, street battles and Nazi rallies; Physical

instruction manuals on such matters as how to sit in an armchair

and how to hold a golf club.

--This

is the strange montage of noble and grotesque visual ephemera

that filled Francis Bacon's studio and his mind. It is up to academic

art historians to fret over the exact correlations between particular

photographs and paintings.

--What's

surely beyond dispute is the overall match between the photographic

museum nested in chaotic piles and boxes in Bacon's studio and

the uniquely uncomfortable world of his paintings.

--In

meditating continually on this strange mix of images he generated

his own painted reality - at once grandiose, Kitsch, horrible,

magnificent and modern, a painterly mirror of the 20th century

whose archetypal relic, the photograph, was his primary research

tool.

--In

the end, the reason we look at these tattered and crumpled and

marked images, the reason his studio is preserved as a holy- or

unholy - sanctum in Dublin, the reason his Tate Britain retrospective

will stun its beholders ... is that Francis Bacon was a genius

whose paintings are as shocking, sensational, disturbing and rewarding

now as in his lifetime - and will remain so for as long as human

beings look to Art for the "greatest things that man can

feel".

--Francis

Bacon is a Titan, a giant of painting. Look at these images long

enough and a strange frenzied reality - violent, sexual, godless

- flickers in your mind's eye. It is Bacon's reality. Look at

this paintings and that reality forces itself into the very pores

of your skin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

--Oil

painting is so subtle, he insisted - it creates effects impossible

in any other art. Francis Bacon's paintings include achievements

that rival and revive for modern eyes those of the Old Masters

he so admired.

--Just

look at the shadows that seem to creep into his impossible rooms

as if from hell itself.

--Look

at his bodies, how they tie themselves in knots, get sucked into

a fourth dimension, crouch and crawl. --They

are Michelangelo's Ignudi put through a meat grinder and they

make you, painfully and scarily, aware of your own body, its needs,

powers, and inevitable fate.

--Francis

Bacon is an atheist with a sense of Hell whose paintings have

the scale of imagination of the Sistine Chapel.

--To

look through his photo-hoard is to travel, stumbling, behind a

Mind on Fire!

--Bacon's

sense of the body strikes people who look at his Art, first of

all, as cruel and vicious. He painted his best friends as if they

were maimed first world war soldiers, their faces shattered and

deformed into slabs of ill-sutured flesh with eyes scarily alive

inside the horror mask.

--His

bodies, grappling and broken, can seem merely ugly. One doesn't

fully grasp their beautiful dimension until one looks at some

of his paintings after seeing the many images of the classical

and Renaissance nude in his photograph collection - in reality,

even his most disfigured bodies still have nobility.

--They

are heroic!

--Velázquez

and Rembrandt, those philosophers of the portrait he so worshipped,

portray the very loneliness, pain and brevity of human life as

a heroic fact that makes the least of our actions, the most banal

of existences, courageous.

--Francis

Bacon was brave. His Art is brave and can make us brave.

--In

centuries to come, an artist will pore over reproductions of his

work just as he smeared his paint on Velázquez - in devoted

recognition of a Supreme Master!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|